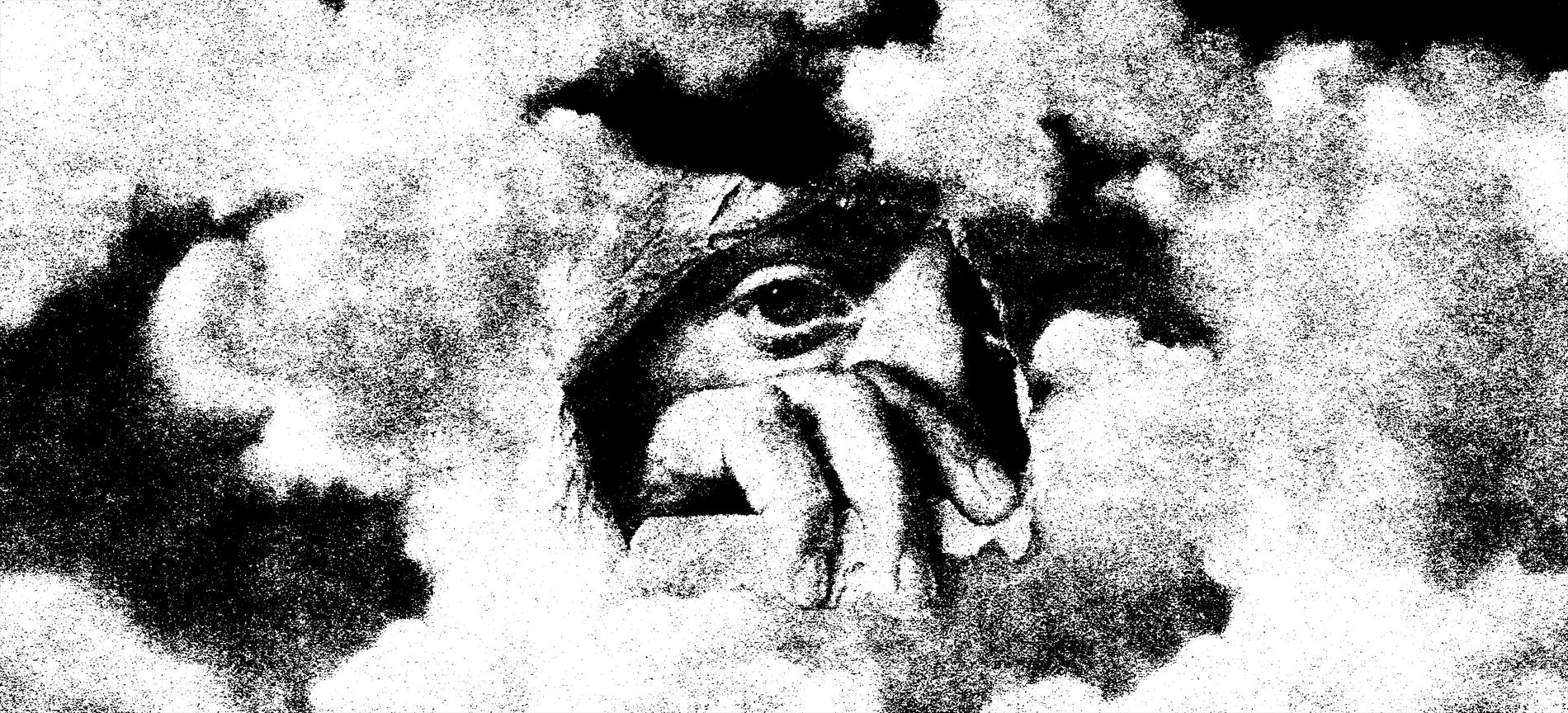

Cuanto más lo pienso, más claro se hace: de este mundo no podemos saber nada.

Estudiar filosofía o ciencia marca el status que tendrán las cosas que se nos presentarán. Todas las apariencias que se nos forman ante los ojos estarán normadas por los ordenamientos del flujo de experiencia con el que crezcamos. Y entonces buscaremos, inútilmente, explicarnos el mundo. Algunos lo harán con la reflexión en mano, otros con un microscopio. Algunos buscarán en el cielo las respuestas a los enigmas del mar, otros se preguntarán dónde es que, de hecho, comienza un océano. Otros tantos, inmersos en sus pizarrones verdes con tizas blancas, intentarán explicarse la realidad desde los símbolos y las reglas de combinación de éstos; otros intentarán construir la razón usando los mismos símbolos, pero reglas sútilmente distintas.

En el fondo, no obstante, estamos presos. Hay una cárcel que nos rodea, si es que de hecho somos algo dentro de otra cosa, que impide que obtengamos la mínima cantidad de información sobre lo que de hecho podría llegar a existir, si es que tal cosa de hecho es.

En nuestros teatros construimos sistemas, teorizamos sobre la otredad y sobre la subjetividad propia. Suponemos grandes marcos de explicación y nos co-reducimos entre ellos. Pero, en el fondo, sabemos NADA. Es como si estuviésemos viviendo, curiosamente, en una suerte de simulación puramente sensorial, donde lo único de lo que podemos estar medianamente certeros es de que sentimos algo, aunque jamás sabremos qué significa ese algo o qué es. La pregunta difícil sobre la consciencia muchas veces se frasea como el tener que responder a por qué es que se siente algo el sentir algo. Pero, en el fondo, la pregunta de la consciencia es la pregunta sobre absolutamente todo lo que hay para nosotros. El mundo que vemos es inmediato.

La prisión en la que estamos, además, puede decorarse. Algunos intentarán decorarla para nosotros. Algunos otros nos obligarán a comprar el decorado que de su elección pasa a norma. Muchos otros destruirán las prisiones en los que se atrincheran quienes rechazan el decorado impuesto. Sí, destruir la prisión es destruir la vida.

Ironía no es que la palabra célula dimane directamente del latín cellula, que fue una palabra utilizada para designar habitaciones pequeñas, usualmente para los esclavos de los romanos. Somos células, y vivimos en una, si es que de hecho vivimos.

Y si nada podemos saber, ¿qué podemos hacer? Este mundo se antoja, de pronto, como una constelación de alucionaciones interactuantes entre sí.

Nos casamos con nuestros aparatos teóricos y desde ahí dictamos el mundo. Un mundo que existe, únicamente, en la sensación. Pero la sensación no es suficiente para determinar que todo existe, incluyéndonos, pues bien ésta podría ser inyectada o extracta desde otros lugares fuera del espacio-tiempo, otras realidades base. Pero nada tiene sentido, porque ni siquiera podemos saber de qué están hechas las paredes de nuestra celda, sólamente podemos sensarla con las manos. Nunca ante los ojos, sólo ante el ir a tientas, gateando.

Cuando establecemos una vida en la intelectualidad estamos, en cierta forma, decidiendo cómo sentir la celda. No, esta vez no vamos a sentir los fríos barrotes, sino que vamos a estudiar el suelo. Vamos a teorizar sobre ellos, y vamos a usarlos. El mundo se construye en barrotes, y todos son reducibles a barrotes interconexos.

Sorpresa, pues, que nadie nunca ha sabido qué es un barrote, porque de lo único de lo que estamos medianamente convencidos es de cómo se siente un barrote.

Muy fenomenólogo de mi parte, sí, pero el problema no es volver a teorizar sobre el mundo. Es traer a cuenta que los problemas ya discutidos por Peirce, James, Goodman y tantos otros son, nuevamente, formas de adornar la celda. Yo quiero escapar de ella, aunque tengo la sospecha de que, de hecho, YO SOY la celda. No una forma fachera de decir que soy el universo experimentándose, sino que, de hecho, la única forma de existencia es la del encierro. Terrible referencia a la clausura metabólica, porque de hecho para existir, parece ser, debe uno encerrarse. Vivir es nunca poder ser libre. Ser un organismo es, siempre, ser la celda. Y en la celda nada existe realmente, sólo aquello que la celda ya permite affordear.

Y si a esas vamos, entonces: ¿de qué mundo hablamos? ¿qué cosa es lo que nos excede? Posiblemente nada, posiblemente nada que una cosa clausurada pueda entender. Creo, ahora y no como antes, que para experimentar el mundo como es, el primer paso es no poder experimentarlo. Ser un cogniton es, para siempre, el encierro. En el mundo, lo único que es como es es aquello que nunca puede saber lo que es todo lo demás, ni esa misma cosa. Esta es una censura, enorme. Y para vivir, dentro de la censura, hay que crear ficción. La ficción está en la celda. Somos prisioneros de la vida, de la organismidad. Somos prisioneros del mero hecho de ser.

La libertad trae consigo la absoluta imposibilidad agencial. Ineficacia causal total. Sin cognición, a lo más computación.

No puedo entender todavía qué de bello tiene organizarse en una cosa viva. Lo único que sé es que, al dejar de serlo, tampoco podré entender lo que es el todo. Y todas las ideas que haya tenido habrán servido para decorar mi celda y acercarme a quienes tienen celdas parecidas.

Primera tesis: la clausura metabólica implica la separación del sustrato mínimo, el cual se hace inaccesible.

Consecuencia de la tesis: un ente cognitivo (cogniton) es siempre incapaz de acceder al sustrato mínimo por sus propia capacidad de invarianza organizacional.

O tal vez somos fantasmas en la máquina y en realidad, el mundo del significado pleno está afuera de la celda, donde la cognición absoluta debe existir. Veremos después.

— extremeEnd

The more I think about it, the clearer it becomes: from this world, we cannot know anything.

Studying philosophy or science determines the status of the things that will present themselves to us. Every appearance that forms before our eyes will be governed by the structures of experiential flow in which we grew. And so we will seek, in vain, to explain the world. Some will do so with reflection in hand, others with a microscope. Some will look to the sky for answers to the mysteries of the sea, others will ask themselves where, in fact, an ocean begins. Many, immersed in their green chalkboards with white chalk, will try to explain reality using symbols and the rules for combining them; others will try to build reason using the same symbols but slightly different rules.

Deep down, however, we are imprisoned. There is a prison surrounding us—if we are indeed something inside something else—that prevents us from obtaining even the tiniest amount of information about what might actually exist, if such a thing even does.

In our theaters, we build systems, theorize about otherness and our own subjectivity. We suppose grand frameworks of explanation and co-reduce ourselves within them. But at the core, we know NOTHING. It is as if we live, curiously, in a purely sensory simulation, where the only thing we can be remotely sure of is that we feel something, even though we will never know what that something means or what it is. The hard question of consciousness is often phrased as having to answer why feeling something feels like something. But fundamentally, the question of consciousness is the question about absolutely everything that exists for us. The world we see is immediate.

Moreover, the prison we inhabit can be decorated. Some will try to decorate it for us. Others will force us to buy the decor that, by their choice, becomes normative. Many will tear down the prisons in which those who reject the imposed decor barricade themselves. Yes—destroying the prison is destroying life.

It’s not ironic that the word cella derives directly from Latin cellula, which was used to denote small rooms, usually for Roman slaves. We are cells, and we live in one—if we live at all.

And if we can know nothing, what can we do? This world suddenly appears as a constellation of interacting hallucinations.

We marry our theoretical apparatuses, and from there we dictate the world. A world that exists only in sensation. But sensation is not enough to determine that everything exists, including ourselves, since it could be injected or extracted from places outside space-time, other base realities. But nothing makes sense, because we cannot even know of what our cell’s walls are made; we can only sense them with our hands. Never with our eyes—but by groping and crawling.

When we build a life in intellectuality, we are, in a sense, deciding how to feel the cell. No—this time we will not feel the cold bars; we will study the floor. We will theorize about it, and we will use it. The world is built on bars, and all bars are reducible to interconnected bars. Surprise, then, that no one has ever known what a bar is, because the only thing we are somewhat convinced of is how it feels.

Very phenomenological of me, yes—but the problem isn’t theorizing the world again. It’s bringing to light that the problems discussed by Peirce, James, Goodman, and many others are, once more, ways of decorating the cell. I want to escape it, though I suspect that I AM the cell. Not as a flashy way to say I am the universe experiencing itself, but that the only form of existence is that of enclosure. A terrible reference to metabolic closure, because to exist, it seems one must lock oneself in. To live is to never be free. To be an organism is always to be the cell. And inside the cell, nothing truly exists—only what the cell already affords.

And if that’s the case, then: what world are we speaking of? What thing exceeds us? Possibly nothing—possibly nothing that a closed thing could ever understand. I now believe, differently than before, that in order to experience the world as it is, the first step is to not be able to experience it. To be a cogniton is forever to be imprisoned. In the world, the only thing that is as it is is that which can never know what everything else is—nor itself. This is an enormous censorship. And to live within censorship, one must create fiction. Fiction is inside the cell. We are prisoners of life, of organismality. We are prisoners of mere being.

Freedom brings with it the absolute impossibility of agency. Total causal inefficacy. Without cognition—at most, computation.

I still cannot understand what beauty there is in being organized into a living thing. The only thing I know is that, upon ceasing to be one, I will be unable to understand what the whole is either. And all the ideas I have will have served to decorate my cell and bring me closer to those whose cells are similar.

First thesis: metabolic closure implies the separation of the minimal substrate, which becomes inaccessible.

Consequence of the thesis: a cognitive entity (cogniton) is always incapable of accessing the minimal substrate by virtue of its own organizational invariance.

Or perhaps we are ghosts in the machine and, in reality, the world of full meaning lies outside the cell, where absolute cognition must exist. We will see about that later.

— extremeEnd

Leave a Reply